(Last of two parts)

Resbak. I liked how he put it. The kosa not only gave the street slang such a surprisingly apt communal take, but he spiked a certain militant, no-nonsense edginess to it as well. It actually struck me like some earnest tribal wisdom. If we would only humbly allow it, we could always learn great things from the masses; with resbak, I found myself mouth agape doing a double take.

At any rate, I threw Kosa D a stinging high-five, confident that he and the kosas fully understood my report: that an otherwise loose but conscious community of urban intellectuals -- writers, artists ad cultural workers -- has found common urgent cause in defending -- indeed in coming out to resbak behind – one of its own.

Yet prior to my illegal arrest and detention, I had long and pretty much accepted that, for all its intents and purposes, I had already been a rather obscure, almost estranged member of this community. This had been a consequence among the many trade-offs, so to speak, in choosing to work fulltime in the anti-feudal, anti-fascist and cooperative movement of poor peasants and farm workers in the countryside.

Being uprooted from one’s immediate and familiar milieu was, in fact, a sacrifice of considerable weight. I would, quite naturally in the beginning, spend sleepless nights in that proverbial tug-of-war somewhere within the petty-bourgeois quarters of the self. But all around me, the sheer realness, the undeniable concreteness of an utterly backward and god-forsaken rural world transforming itself into a bulwark of all-round social change would just as soon prove to be too much of an irresistible pull.

There was romance to it too, of course, and as a poet, nothing of the earthy images of ricefields and barefoot children, nor the primal sounds of crickets and crows ever escaped me. There would be times, however – and these I think were moments of lucid self-appraisal – when it seemed as if I had somehow escaped poetry.

There was romance to it too, of course, and as a poet, nothing of the earthy images of ricefields and barefoot children, nor the primal sounds of crickets and crows ever escaped me. There would be times, however – and these I think were moments of lucid self-appraisal – when it seemed as if I had somehow escaped poetry.

The countryside is not just a series of poignant images. It is, rather, a burning vision of class conflict and chaos as it is, at the same time, a clear and wide vista to an otherwise elusive genuine peace. It is not just a chorus of natural sounds – the fury of war escalates and resonates in high fidelity, even as the sure rhythm of emancipation ascends and becomes a most contagious beat. The countryside is a whirlwind and I had great difficulty finding the time to pull myself aside and render its movement in the most precise and powerful poetic language that it ultimately deserves.

More plausibly though it was not time alone that I had not enough of but simply the faculty and even the drive to pull it all off. It was a humbling realization – one of so many, in fact, that I certainly owe to the countryside – to learn that I was still quite far from being the dexterous and passionate revolutionary poet that I had once believed myself to be.

I had gone to the countryside not solely out of youthful passion anyway and definitely not just for the muse. More compellingly and in the first place, it was because a scientific knowledge of and attitude to society and history had told me to do so.

Red hymns and marches that so romantically exalt the toiling masses as a social and political force all sound true and beautiful precisely because the mass line is one of history’s most scientific propositions. Agrarian revolution, the peasant war, more than just a source of great literature, are all part of an entire and ongoing historical project which, according to concrete analyses of concrete conditions, is absolutely necessary and highly realizable even within my lifetime. The countryside is at the heart of an applied social science of the highest kind, the goal of which is food on every table and an unprecedented humanity that may just allow for, among other things, a more universal enjoyment of poetry.

Red hymns and marches that so romantically exalt the toiling masses as a social and political force all sound true and beautiful precisely because the mass line is one of history’s most scientific propositions. Agrarian revolution, the peasant war, more than just a source of great literature, are all part of an entire and ongoing historical project which, according to concrete analyses of concrete conditions, is absolutely necessary and highly realizable even within my lifetime. The countryside is at the heart of an applied social science of the highest kind, the goal of which is food on every table and an unprecedented humanity that may just allow for, among other things, a more universal enjoyment of poetry.

In a very comprehensive way, the countryside indeed, was too much of a pull that soon, its far-flung villages, the emergent bastions of real democratic political power, would become my immediate and familiar milieu; soon, work would become home.

I would of course at times imagine myself – and even plan about it methodically – showing up unannounced at some gathering somewhere in Manila where friends and erstwhile colleagues would all be in attendance for old time’s sake. But the ever-present demands of work and some other related considerations seldom offered me the chance. I just had to content myself with those few, very rare small-group reunions where I had managed to sort of sneak into over the years. There were no letters that I could now remember; online communication could always be cursory and somewhat awkward (lingering, lurking a group’s thread I found too stalkish and voyeuristic); text messages were almost exclusively for red-letter days. And so, it’s just so incredibly awry and ironic for me, really, that it took a fascist act of the state to fling me back to the full mainstream consciousness of my former peers and erstwhile community.

Now I think the AFP never quite accurately anticipated how far this community would respond. They may have even arrogantly underestimated the sharpness of reason, the firmness of conscience that writers and artists are just too capable of articulating in the face of patent injustice. I guess the AFP and other concerned state agencies would now have their hands full as it is not just me in particular that the community is standing and doing the resbak for, but the rest of the country’s hundreds of political kosas and the thousands more who have fallen victim to various forms of state repression and terror.

U2’s Bono has a rather fancy sounding Irish equivalent to resbak’s community spirit. He once used the word “meitheal” to rally European business and civil society around his largely philanthropic and utopian campaign to end poverty and hunger in Africa. I have yet to research on the Irish peasant roots and context of meitheal which I’m sure it has, but what I’m fairly competent with right now is tiklos and aglayon – the Winaray terms for mutual aid and farm labor exchange. Both are at the forefront of the production cooperative movement of poor peasant associations which has long served as indispensible counterpart to the militant campaigns to distribute land, reduce land rent, raise farm workers’ wages, eradicate usury, and end all other forms of feudal and semi-feudal exploitation.

This very same cooperative practice in production and rural economy is called luyo-luyo in the Bicol provinces. In the Tagalog regions, it’s either suyuan or the more commonly known bayanihan. It is this kind of militant, collective struggle that has slowly but surely, been moving genuine land reform forward, independently of and fundamentally opposite to the state’s deceptive programs in confronting the country’s centuries-old agrarian problem.

It is this bayanihan movement of the masses that is, in fact, the main target of the current militarist “counter-insurgency” design to which the regime, for obvious demagogic reasons, has appropriated the exact communal name. I don’t know where I stand chronologically, statistically, but surely the list of human rights violations (HRVs) under the Aquino’s Oplan Bayanihan is growing each day and in increasingly alarming pace, brutality and impunity. It was my last job to comprehensively document military atrocities in Barangay Bay-ang in San Jorge, Samar, before I myself became an entry in the HRV roster. It is this tragic irony, I believe, beyond my being a writer and artist, that has given the community the clearest reason and the most urgent motive to call for my immediate and unconditional release.

It is this bayanihan movement of the masses that is, in fact, the main target of the current militarist “counter-insurgency” design to which the regime, for obvious demagogic reasons, has appropriated the exact communal name. I don’t know where I stand chronologically, statistically, but surely the list of human rights violations (HRVs) under the Aquino’s Oplan Bayanihan is growing each day and in increasingly alarming pace, brutality and impunity. It was my last job to comprehensively document military atrocities in Barangay Bay-ang in San Jorge, Samar, before I myself became an entry in the HRV roster. It is this tragic irony, I believe, beyond my being a writer and artist, that has given the community the clearest reason and the most urgent motive to call for my immediate and unconditional release.

To all my resbaks and those of other political prisoners, to all those who realize the true unadulterated meaning of bayanihan, I extend my gratitude straight from the heart. The poet Saul Williams’ heart, as he had it printed once on his shirt right in the middle of the chest, was the African continent. I’m thinking we could actually start a fad by printing or embroidering the Philippine archipelago upside-down on T-shirts to symbolize the heart of the people yearning for justice in a social system gone topsy-turvy; or this could, in fact allude to the historical task of the masses to invert the so-called social triangle. But I feel I’m just stalling the end of this jailhouse blog entry. What I’d like to say finally is that my heart, more than ever, has taken the shape of an unyielding clenched fist.

---------------

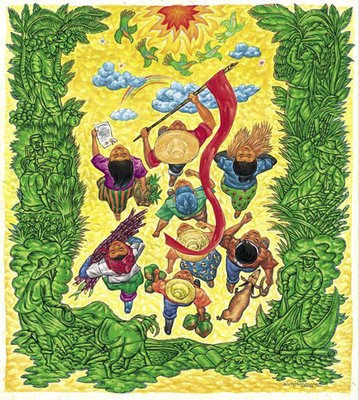

paintings by Boy Dominguez

No comments:

Post a Comment